After years of post-Schrems II case law and increasing scrutiny from authorities such as the CNIL, the use of American tools in Europe has become an exercise in surgical precision.

It is in this context that a ruling from the Administrative Court of Hanover, dated 19 March 2025, has become a landmark case across the industry.

Its conclusion leaves no room for interpretation: loading the Google Tag Manager (GTM) script from Google’s own infrastructure requires prior consent.

Case Study: noz.de — the Requirement for Valid Consent

To fully grasp the scope of this judgment, let’s go back to its origin: the website noz.de.

Like countless publishers, the site loaded the gtm.js script directly from Google’s servers via www.googletagmanager.com. That GTM script then loaded the CMP (the consent banner).

The direct consequence was clear: a connection with Google was established before the user had any opportunity to make a choice.

The Court also found that, even after consent was collected, the subsequent data processing lacked a valid legal basis — solely because the consent gathered through noz.de’s Sourcepoint CMP was itself invalid.

In other words, the Court did not rule that using Google Tag Manager is illegal per se; rather, it found the implementation on noz.de unlawful for two cumulative reasons:

- Consent was not obtained before loading GTM.

- When consent was finally obtained through Sourcepoint, it was invalid because it failed to meet certain GDPR requirements.

The Court’s conclusion could not be clearer: to be lawful, loading GTM from Google’s infrastructure must depend on consent that is both prior and valid.

We won’t dwell here on the validity criteria — they are self-evident to Sirdata, its partners, and its clients. Instead, let’s dig deeper into the requirement for prior consent.

A Surprise? Not Really

This prerequisite for consent actually mirrors the terms of service of GTM itself:

Likewise, Google Ads’ Data Processing Terms (DPA) explicitly confirm that data processing applies to:

The takeaway is unambiguous: this judgment merely reiterates the contractual obligations set by Google itself. Consent is not a bureaucratic detail — it is the cornerstone legitimizing the use of gtm.js loaded from Google’s servers.

Why Exactly? Two Legal Locks to Unlock

The Court based its reasoning on two distinct pillars — two “locks,” so to speak.

The first stems from the ePrivacy Directive (the law on cookies and other trackers); the second, from the GDPR.

We are not lawyers and do not provide legal advice. That said, as experts at the technology ↔ law interface, we can unpack the technical underpinnings of this decision and recommend concrete implementation actions to optimize your setups in light of this new case law.

Lock #1 – Local Storage on the User’s Device (ePrivacy Directive)

gtm.js script from www.googletagmanager.com triggers local storage within the user’s browser.Under ePrivacy, any access to or storage of information on a user’s device requires consent — unless it is strictly necessary to deliver the service requested.

Under ePrivacy, any access to or storage of information on a user’s device requires consent — unless it is strictly necessary to deliver the service requested.

The technical explanation : the “Cache-Control” header, a cousin of the cookie.

How can there be “local storage” if no cookie is dropped? The answer lies in Google’s response headers, particularly the HTTP directive Cache-Control: private.

When Google’s infrastructure delivers the script, it instructs the browser via HTTP headers. You may already know one of these headers — Set-Cookie — the command that tells the browser to create and store a cookie.

Cache-Control: private works in a similar way: it tells the browser to keep its own copy of the file in a private cache. That instruction constitutes storage on the device.

Technically, this mechanism could be used to store a unique identifier and track a user just like a cookie, which is why it falls under the “other trackers” category defined by law.

In short: even without cookies, the act of storage is proven and therefore requires consent.

Lock #2 – Transmission of the IP Address (GDPR)

www.googletagmanager.com transmits the user’s IP address to Google, which operates the infrastructure handling that request.Since an IP address is personal data, its collection and logging (even briefly) constitute processing under the GDPR.

Given Google’s economic model based on data exploitation for advertising, the Court concluded that this processing must rely on consent.

The legal reasoning: to be lawful, any processing must rest on a legal basis — consent or legitimate interest, for example.

Here, the Court decided that the privacy risks for the user outweigh the site operator’s interest. The potential scope of Google’s downstream data use was deemed too broad, making prior consent the only appropriate basis.

Crucially, the Court did not reject “legitimate interest” as a principle, but because of who the data recipient is and what they might do with it.

Legitimate interest remains entirely valid in other contexts — notably when data is not shared with an advertising giant.

From Compliance Burden to Strategic Opportunity

Now that we understand why the Court reached this conclusion, let’s look at how to optimize tag management with compliance as the starting point rather than an afterthought.

Option #1 – Simplicity, with Trade-Offs

The simplest solutions often come with heavy sacrifices.

- Load GTM only after consent: this is the most straightforward and legally safe approach: wait for an explicit “yes” before firing the GTM script. That’s the route noz.de appears to have taken.

- Benefit: legal certainty.

- Downside: massive data loss — no tag, even legitimate ones, can run without consent. Users who ignore or refuse the banner become invisible, skewing analytics and campaign measurement.

- Switching Tools: another radical path is to abandon GTM in favor of another platform, such as the French solution Commanders Act.

- Benefit: addresses compliance at the source and allows tag control based on consent type.

- Downside: costly migration, technical debt, and the loss of GTM’s ecosystem and know-how.

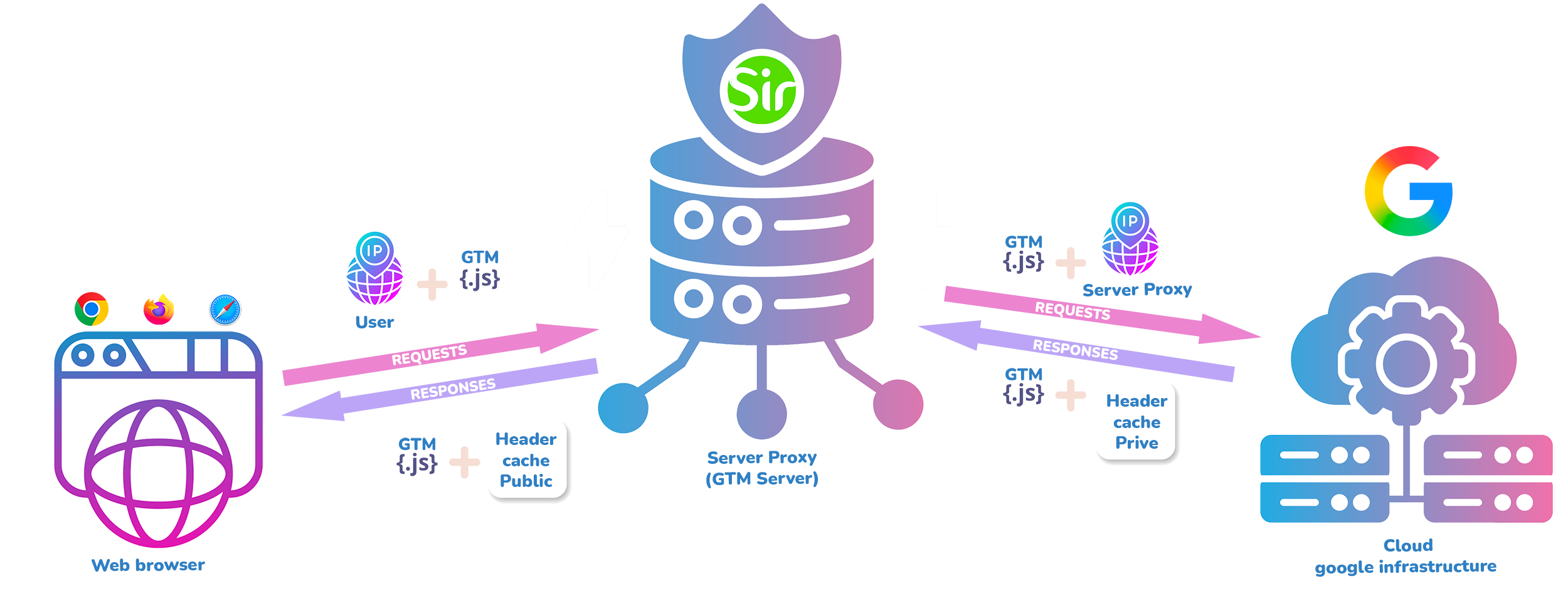

Path #2: The Proxification Strategy

If you’ve realized that the issue lies not in the gtm.js script itself but in the way Google serves it, you can probably guess the remedy.

The idea is to prevent users’ browsers from communicating directly with Google by inserting a proxy server acting as an intelligent intermediary — a compliance filter.

This method directly targets the two “locks” identified by the Court.

How proxying unlocks Lock #1 (ePrivacy storage)

The root of the issue is the Cache-Control: private directive. Legally, it is interpreted as Google instructing the browser to store data on the user’s device — which is exactly what triggers ePrivacy obligations.

The solution? Neutralize that instruction.

A proxy can intercept Google’s response and rewrite the header, replacing Cache-Control: private with Cache-Control: no-store.

That simple modification removes the storage directive altogether.

However, note that Cache-Control: no-store forces the browser to re-download the script on every page load.

If you are pursuing an eco-design approach or are required to adopt sustainable-resource measures, you may prefer Cache-Control: public, which enables shared caching (for instance by ISPs or public network nodes).

The nuance matters: even with a public directive, the browser may still choose to cache for performance reasons — but the intent changes.

Storage now occurs under the user’s control, not by order of the site or its partner, and no individualized tracking is technically feasible.

In short, the act that required consent simply disappears.

How proxying unlocks Lock #2 (GDPR – IP transmission)

When the user’s browser sends a request (and thus their IP address) to the proxy, it is the proxy that subsequently contacts Google — using its own IP. The user’s personal IP remains hidden and never reaches Google’s infrastructure.

This is not a gimmick but a genuine compliance architecture. Sirdata first formalized this proxy approach in March 2022 to address trans-Atlantic data-transfer issues linked to Google Analytics, and its robustness was officially acknowledged by the CNIL in June 2022.

The same legally validated logic applies perfectly here.

In summary, to allow gtm.js to load without prior consent, the proxy acts as a compliance filter that:

- Anonymizes anonymizes the request by masking the user’s IP address; and

- Neutralizes local storage by rewriting the

Cache-Controlheader.

The Practical Solution: Google Tag Manager Server-Side

This proxying principle may sound complex, but there’s already a tool built for precisely that: Google Tag Manager Server-Side (GTM Server).

Its very purpose is to sit between the user’s browser (client-side) and downstream services (such as Google’s infrastructure or ad platforms).

It is therefore the natural place to strip user IPs from requests and to adjust response headers like Cache-Control, either through a custom layer such as Sirdata’s or via a CDN.

But beware: GTM Server is not a silver bullet. Here lies the biggest trap.

The Critical Question: Where Is Your Server Hosted?

GTM Server is merely software — it needs hosting somewhere.

By default, Google promotes a one-click deployment on its own Cloud Run (Google Cloud Platform – GCP).

And that’s precisely where the logic collapses.

Following the strict reasoning of the Hanover Court, compliance is still not achieved. The GTM Server instance that masks the user’s IP only comes into play after that IP has already been received and processed by lower layers of Google’s hosting stack — load balancers, firewalls, access logs, and so on.

In other words, the user’s IP is still transmitted to Google’s ecosystem. The very issue condemned by the Court remains unresolved.

Hence the clear conclusion:for GTM Server proxying to qualify as a full compliance solution — enabling script loading without prior consent and without functional loss — it must run on infrastructure entirely independent of Google.

The same principle applies if your provider itself relies on GCP.

You may of course choose to load GTM via GCP after consent, but only sovereign-by-default solutions, such as Sirdata’s, guarantee the technical and legal isolation required to prevent Google from ever accessing the user’s IP address during script loading.

It is technically possible to complement GCP with an anonymizing Content Delivery Network (CDN), but in that case the IP is always stripped — even after consent — which may break downstream tags such as Meta’s CAPI.

To help you decide how to proceed, we’ve compiled the table below from official documentation and publicly available communications:

| Solution | Infrastructure | Local storage |

IP masking |

Loading without consent |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCP / Cloud Run | GCP | No | No | No | An anonymizing CDN is possible, but the IP address is not usable in sGTM. |

| Addingwell Stape.io (Global) |

GCP | No | No | No | An anonymizing CDN is possible, but the IP address is not usable in sGTM. |

| Taggrs Stape EU |

EU Cloud Providers (non-Google) | No | Yes | No | Non-anonymizing CDN possible. |

| sGTM by Sirdata | EU Sovereign Infrastructure |

Yes | Yes | Yes | – |

Comparative Overview

The Google Ecosystem (GCP, Addingwell, Stape.io Global …)

These setups rely entirely on Google’s cloud infrastructure. The user’s IP is inevitably transmitted to Google before any processing occurs. They unlock neither of the two compliance “locks” and therefore require prior consent — or must be paired with an anonymizing CDN (which can disrupt CAPI tags).

European Hosts (Taggrs, Stape EU)

These providers offer a partial but meaningful answer.

By using European infrastructures distinct from Google’s, they solve the IP-transmission issue (Lock #2) — a major step forward.

However, they do not natively rewrite the Cache-Control header. Lock #1 therefore remains closed, meaning consent (or a CDN) is still required.

The Integrated European Solution (sGTM by Sirdata)

A sovereign-by-design solution that goes further.

Hosted on independent European infrastructure, it natively addresses both issues: it masks the user’s IP and rewrites the Cache-Control header.

It is the only self-contained service unlocking both compliance locks simultaneously, making GTM loading without prior consent both technically and legally achievable.

So – What “Consent” Are We Talking About?

For clients and CMP users opting for post-consent loading, one final question remains:

what does it actually mean to “collect consent for GTM”?

Strictly speaking, users do not consent to a tool but to data processing activities.

Therefore, the consent required to load gtm.js from Google’s infrastructure must cover Google’s own advertising activities.

Under the industry standard — the IAB Europe Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF) — this translates quite precisely into:

- Vendor #755 (Google Advertising Products); and

- Purposes #1 (“Store and/or access information on a device”) and #2 (“Use limited data to select advertising”).

Note that this initial consent merely unlocks the GTM container.

Each tag you fire through GTM — Meta, Criteo, and others — must still be conditioned on its own valid consent, aligned with its respective vendors and purposes.

Think of it as a key that opens the building entrance (the GTM container), while each apartment inside (each tag) still requires its own key.

Consent management is therefore not a simple GTM “on/off” switch but a fine-tuned orchestration that must be carefully implemented within your CMP.

Sirdata GTM Server-Side

sgtm.sirdata.io

Start today with Sirdata sGTM — the sovereign-by-default way to combine compliance and performance.