Today, many technical and legal changes are underway in the digital ecosystem.

Between the new directives that reinforce the protection of the user's personal data (GDPR) and the end of third party cookies planned by Internet browsers, the actors of the advertising and digital marketing sector are in full search of solutions and alternatives.

It is becoming difficult for some players, especially publishers, to know what is best to apply for the monetization of their website.

Although there are already many alternatives proposed by someworking groups (coordinated by the IAB, Criteo, Google etc.): contextual targeting, Privacy Sandbox, Project Rearc, or initiatives such as Universal ID etc., it remains difficult to know what is the best way to monetize a website. As of today, these solutions are not yet validated from a legal point of view.

This is notably the case with the Cookie Wall, whose implementation raises many questions.

All these changes and new developments are creating confusion for professionals in the digital ecosystem and Internet users.

What is a cookie wall?

The cookie wall is a practice which purpose is to block access to a site or application to the user as long as he has not carried out a voluntary action such as consenting to the use of trackers and the use of his personal data for advertising purposes, or subscribing, registering for the newsletter or website service...

Why did publishers start using cookie walls?

Publishers are struggling to monetize their websites because of the regulations that are gradually being put in place, bringing them into a legal as well as technical limbo.

That's why tools like the cookie wall have been developed so that publishers can continue to monetize their websites.

Is the use of cookie walls a viable practice over the time?

Blocking a user's access to a website and forcing him to make the choice of consenting or subscribing to its site, for example, is a way of forcing the user to perform an action, which seems to be contrary to the requirements of the legislation in force.

In this sense, such a technique cannot be perceived as an appropriate solution in time.

Is the use of Cookie Walls contrary to the law?

This question is the subject of many debates and seems complex to determine.

Indeed, consent has been defined by the General Data Protection Regulation as "any free, specific, informed and unambiguous expression of will by which the person concerned agrees, by a declaration or by a clear positive act, that personal data concerning him/her may be processed".

Obtaining consent or not, must not equal to limiting access to a service. It is in this respect that the cookie wall could be considered as a solution non respectful of the legislation.

Indeed, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) adopted guidelines in May 2020 that stipulate cookie walls are not a valid means of obtaining consent. Since, as the EDPB mentioned, valid consent must be freely given, cookie walls do not necessarily leave users a real choice.

The CNIL declared yet the same point of view in 2019 by prohibiting the use of cookie walls. Following this decision, the Council of State in its decision of June 19, 2020 stated that the CNIL, in considering that access to a website could not be subject to the acceptance of cookies, has engaged in what is called an "excess of power" and therefore did not respect the limits assigned to it by the Constitution or by law.

Faced with this judgment of the Council of State, the CNIL reformulated its request to the market in these new guidelines adopted on September 17, 2020, where it states that "the fact of subordinating the provision of a service or access to a website to the acceptance of writing or reading operations on the user's terminal (a practice known as "cookie wall") is likely to infringe, in certain cases, on the freedom of consent".

In certain cases?

This term mentioned by the CNIL does not mean a generalized authorization of the cookie wall.

The rule therefore remains the prohibition and its legal use remains the exception and is subject to validation by the CNIL.

What other practices are similar to the cookie wall?

The Paywall :

It is a practice that consists in restricting the access to some of contents of a webiste contents (such as articles from press sites for example) or even restricting full access to the website to an Internet user, if the latter has not taken out a subscription.

The Paywall (used for several years already by certain media) is now considered as a real optionto limit the use of cookie walls that seem to violate the notion of free consent.

The service provided by the website becomes payable either in cash or financed by the advertising data.

This solution seems interesting, however and unfortunately, it cannot be used by all publishers, because some do not have sufficient content or service for Internet users to accept to subscribe.

How does it work?

Most often, the paywall will be activated if the Internet user does not have anaccount or as called a "premium" account and refuses the advertising purposes proposed by the site.

The Internet user can then be offered a restricted access to the content of the site, for example by being exposed to a banner quite largely limiting the visibility of the site.

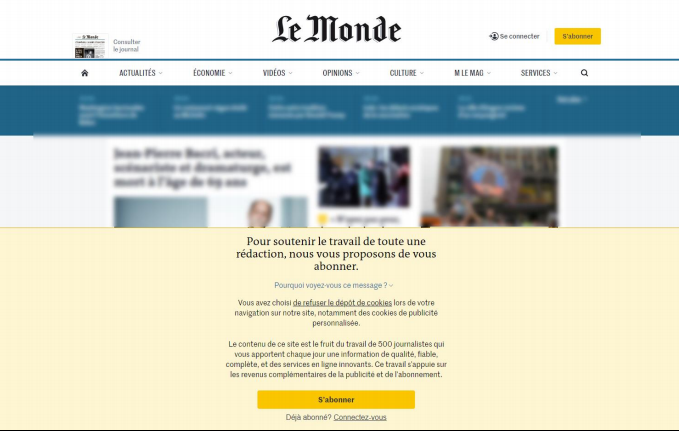

This is notably what the two publishers L'Obs and Le Monde have recently implemented, by imposing on their sites a wide banner that covers more than a third of the web page on computer and half of the screen on mobile environments when the user does not wish to subscribe or consent to the use of his personal data for advertising purposes.

The log wall :

Logging in is, this time, a practice that consists in allowing a user to identify himself to a website in order to access the content.

It is once again an interesting solution because it would allow publishers who do not have the necessary content for a subscription proposal to set up an alternative. This being said, the problem mentioned for the use of the Paywall can also be found in this case. Indeed, if a site does not have a sufficiently attractive content, it will be difficult for it to push users to create an account.

On the other hand, from a legal point of view, publishers will have to pay great attention to the balance they will propose to the user. For the alternative to be viable, wouldn't the creation of a user account mean the non-use of any tracker and personal data? The use of these techniques is still subject to validation by the CNIL in France.

These techniques are evolving, proposals and A/B tests are multiplying, but it seems clear that they are not the perfect solution for players in the advertising and digital marketing sector.

These three practices (Cookie Walls, Paywalls and Log Walls) are therefore subject to a real legal uncertainty that remains to be clarified by regulators in the coming months.

And in other European countries?

These various questions concerning the good practice(s) to be used are being discussed all over Europe.

For example, the use of Cookies Walls is not a case reserved for French publishers. We note that questions about its use are indeed present beyond our borders.

However, for other countries, the answer regarding the legality of cookie walls has been clearly stated, since, whether it is the British ICO , the Dutch AP or the Spanish AEPD, these data protection agencies decided that cookie walls are not legal or authorized because they do not offer a real alternative to consent.

As they stand, therefore, all of these alternatives cannot be considered as "miracle" solutions.

And, especially, since regulators have yet to make a clear statement about them. It is highly likely that the next few months will be rich in evolutions but it is still impossible to take a definite decision on this issue at this time.

For more information, find our complete article on the post-cookies world here (FR):